It is an area of mystery, a great blue expanse that surrounds us, womb-like, filled with curious creatures.

Some of the inhabitants of this blue realm, like the marlins, have 3-foot-long, unicorn-like swords on their noses. It is a place where secretive beaked whales prey on giant cephalopods, the squids, in the cold and inky blackness.

In its warm upper reaches, closer to the surface, pilot whales and dolphins, lightning-fast wahoos, and 10-to-12-foot-long oceanic nomads, whitetip sharks, patrol and wander the open expanse in search of a meal or a mate.

This is our backyard. Only now are we beginning to scratch the surface of what is out there in our waters. In its deeper reaches, in the dark abyss, we still know almost nothing.

Even the eyes can be deceiving. Out in the great blue expanse, just over the horizon where we cannot see and where most of us rarely visit, lies the majority of the Cayman Islands and in some ways, it has come to define us.

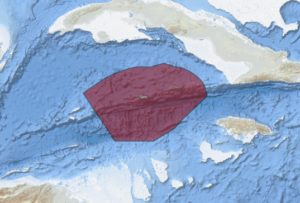

40,000 square miles of deep blue sea

In January of this year, Kelly Forsythe began working as a policy and coordination officer at the Department of Environment, focusing on an area 300 times the size of all the land area in the Cayman Islands combined. That’s 40,000 square miles of deep blue sea known as ‘Cayman waters’, along with the resources within it, and the deep seabed that extends out from the shallow inshore environment to the outer limits of the Cayman Islands Exclusive Economic Zone.

In an interview with Cayman Compass, Forsythe described herself as a multi-generational Caymanian with over six years of experience in conservation and marine research.

Part of Forsythe’s job is to figure out what we have, where we have it, and how much of it we have.

“While the Cayman Islands would be considered a small island state, the marine area around us is vast,” she said, adding, “Much of the deep sea around us is unknown and undiscovered without expensive equipment, as it’s beyond recreational scuba diving limit.”

Forsythe has been given the job to help design and establish the management architecture and the policy for this enormous blue expanse that amounts to over 99% of the Cayman Islands.

“This will not be a one-man job by any means,” she added. “It will require the support and collaboration from within the Cayman Islands government, our neighbouring UK overseas territories and the UK government through the Blue Belt Programme and partners such as Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas), Marine Management Organisation (MMO) and the Foreign Commonwealth Development Office (FCDO).”

The Blue Belt initiative that Forsythe is referring to is the UK government’s flagship international marine conservation programme. Since 2016, it has worked closely with a number of UK overseas territories to assist in the creation and maintenance of healthy and productive ecosystems.

Next year, the Department of Environment will celebrate the 40-year anniversary of the marine parks system in the Cayman Islands, but those parks only protect some areas in the shallow waters around the islands.

Once you get past the ‘drop off’ into deep waters, there is almost no enforcement, hardly any regulations, and not much is even known about the variety and quantity of the fish stocks and marine life that exist in the deep waters around our islands.

“It makes sense to look beyond our current nearshore marine protected areas and consider what else may need to be managed more effectively,” explained Forsythe. “Our planet, our ocean and our Cayman waters and its resources are under more pressure than ever before from climate change, a growing global population and unsustainable practices.”

The Department of Environment knows that they will need help from partners, including the local fishing community, to gain a better understanding of the resources in the deep-sea environment.

“We want to make it clear that through this programme, we value the opinions, concerns and motivations of other groups — especially those that are most impacted by the health of our fisheries,” Forsythe said. “We cannot work in a silo and without consultation.”

According to Forsythe, one of the priority fish species they will be looking at early on is the snapper, a staple on the menus of local restaurants and on the table of many homes.

“We’re particularly interested in our deep-water snapper fisheries, particularly for black, blackfin, silk and queen snappers.”

“Little is known about the life history of these particular fish, and we hope in collaboration with local fishers to find out more, including how big they get, what depth they live at, how often they reproduce, how long they live and how many there are.”

Currently most of the deep-sea fishing that is occurring locally is what is known as ‘recreational or artisanal fishing’, but if local, large-scale commercial fishing activities start occurring in the deep waters around us, then it is likely those fishermen will be subject to international reporting and catch requirements associated with some of the more valuable fish species that could be moving through Cayman waters.

According to Forsythe, a large part of the Blue Belt Programme is to promote and support effective management of marine resources.

“To have an idea of ‘overexploitation’, you first need a baseline to judge it against and for much of our deep-sea resources that has not yet been defined,” she said.

“The responsibility to protect Cayman’s waters, manage its users and monitor their activities falls in the laps of multiple Cayman Islands government departments and agencies, and through the Blue Belt Programme it also extends to include the activities conducted in the Caribbean region, meaning that it also extends to our neighbouring island states.”

Straddling fish stocks

Part of the reason that engagement will be necessary with our local fishermen and other island states is that many of the fish that can be found in Cayman waters are also migratory, meaning they are ‘straddling fish stocks’.

That means they are also passing through the waters of other countries in the region. They are, therefore, considered a shared resource. When and if commercial fishing operations are established in the Cayman Islands, international mechanisms are in place, such as the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), to protect and conserve fish such as tunas and swordfish, so that commercial exploitation is sustainable and the stocks are not overly stressed.

Forsythe said, “We’re working closely with the Marine Management Organisation and the Cayman Islands Angling Club to help get a better understanding of ICCAT requirements and what species this would target and how monitoring might take place.”

Under this programme, it is possible local fishing boats engaged in commercial fishing activities in Cayman waters may one day have to install tracking devices and report catches.

“Part of this work is, of course, to gain a better understanding of the vessels and their activities within our waters, but also to show compliance for treaties/agreements already in place with other nations to further foster collaboration,” she said.

Monitoring and managing the Cayman Islands Exclusive Economic Zone will not be easy and Forsythe conceded that numerous challenges exist, including a lack of human resources and the costs associated with having to patrol such a large space.

“Fuel is expensive, boats break down. Under this programme, with the help of our UK government partners, we’ve been testing out how satellite surveillance might work,” she said.

It is also possible that foreign vessels have or are occasionally actively targeting the marine resources in our waters, and that illegal, unregulated and undocumented fishing activities are happening that we may not even be aware of.

“There have been whispers of suspicious activity and reports of unusual vessels in the past,” she said. “However, as we have previously said, the area we’re talking about is vast and proves more difficult to monitor than our nearshore environment.”

Forsythe believes it will likely require a multi-pronged approach to better understand what is going on in the deep sea environment around the Cayman Islands.

“Despite technology improving all the time, two systems may work better than one –meaning that figuring out where our vessels are (especially the smaller ones) and monitoring them whilst also surveying the wider area could help fill in necessary gaps,” she said.

Forsythe believes that one of the big positives of a potential local vessel monitoring system would be for the safety of the crew themselves.

“If you know where your vessels are, you know where to find them if anything goes wrong,” she said.

Last year, the Compass reported that the UK government was looking to fund a marine radar to improve domain awareness in the waters around the Cayman Islands.

The Compass has asked the Governor’s Office to clarify the current status of the undefined boundaries of the Cayman Islands, with respect to the neighbouring islands of Cuba and Jamaica but, as of publication time, had not received a reply.