Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part series on the origin of the song ‘Dominica, Land of Such Beauty’ by Robert Maguire. The second installation will be publshed tomorrow, Sunday, December 14.

Prologue

When, in mid-November 2025, I drove into a car rental garage parking lot in Pottersville, a suburb of Roseau, the capital of the Caribbean island of Dominica, a mechanic who I’ve known for a while approached the car, smiling, with two little girls following closely behind. When the trio reached the car Keegan Ambrose, the friendly mechanic, turned to the girls and asked, “Do you know who this is?” “Yes,” they both responded, “this is Bob Maguire.”

My eyes widened as I did a double-take. How do these children know me? “What did he do?” Keegan next asked. “He wrote the song, Dominica, Land of Such Beauty” was their immediate response. More amazement.

“Can you sing the song for him?” was his next question. “Yes,” both girls responded, and they started to sing.

I stopped them, interceding with my own question, “Is it OK if I video you on my cellphone while you sing?” The older one, eight-year-old NillyDahlia Ambrose, courteously said, “Yes,” and got ready to start again.

They sang: “Dominica… Dominica…. Dominica, Land of Such Beauty. Your rivers and mountains…, Caribbean Sea…, are all a part of your Dominica beauty,” with NillyDahlia keeping time with her hands, shyly glancing away from the camera, but then confidently back toward it as her three-year-old cousin meandered off camera.

When NillyDahlia completed the verse, I interjected again, thanking her for such beautiful singing. I was delighted to hear such a sweet, sincere rendition of the song I composed in 1969 from a child born 48 years later.

I asked the girl’s father how it was that his daughter had come to learn this song? Keegan explained that she – and her classmates at the Newtown Primary School –were taught it by their teacher so they could perform it for the school’s assembly commemorating Dominica’s November 3rd Independence Day.

The following week, I visited NillyDahlia’s second grade class. Her teacher, Miss Laurant, told me she taught the song to her students because not only does she love it, but also it is a perfect choice for National Day. When I arrived in the classroom, the teacher gathered her students and, accompanied by a recording of the song available on YouTube, she directed NillyDahlia and her classmates to sing several verses. They like singing the song, one said, because it is about their island and “it’s a nice song.”

That those eight-year-olds, born 48 years after I composed the song, could sing it to me when I visited their school was moving, but not completely surprising. Over the years, I’ve been told by several Dominicans that my song has become the island’s ‘unofficial’ national song. Some who I know in Dominica’s overseas Diaspora have made similar remarks.

Given how this song has touched so many people for so many years, I’ve decided to write this story of its birth and evolution.

A Steep Learning Curve

One evening in November 1969, a little more than two months following my arrival in Dominica as a newly minted Peace Corps Volunteer, I sat on the ground level veranda of the two-story house in Pottersville where I rented a first-floor apartment. My acoustic guitar was at my side. Next door, in the yard, was the Swansea Domino Club, whose members filled the evening air with the sounds of laughter, chatter, and tiles slamming down on a table they surrounded, playing the game with heart, soul, and enthusiasm. Sometimes, the boisterous sessions lasted deep into the night.

For my volunteer service, I was assigned to Dominica’s Ministry of Education with the task of creating the island’s first social studies curriculum for its roughly 60 primary schools. With my newly minted Bachelor of Arts degree in Social Studies Education from Trenton State College in New Jersey, I had acquired the basic subject matter knowledge and technical skills to engage my assignment. Social Studies, however, is a subject that draws heavily on knowledge of the context: geography, economy, history, politics, culture, society. My primary school social studies curriculum would have to draw heavily on knowledge of Dominica, something I knew next to nothing about when I arrived there.

I knew I would have to address that important shortcoming right away, so I committed to climbing a steep learning curve about Dominica from the day I set foot on the island. Fortunately, in short order I was guided by a newly composed Social Studies Committee of six primary school teachers who volunteered to work with me and a growing network of acquaintances and friends.

By the time I sat alone on my veranda on that November evening in 1969, strumming my guitar, that curve was streaking like a shooting star across the night sky. In two months, I had travelled around the island, witnessing its incredible natural beauty and meeting friendly, gracious people everywhere I went. I had begun learning about Dominica’s history and the transitional governance path from colonialism to independence it was going through when I arrived. Mandated by British colonial authorities, this period, called Associated Statehood, would end when Dominica

became fully independent in 1978.

And I witnessed National Day festivities in early November with their vibrant manifestations of the island’s music, song and dance. As my knowledge about Dominica advanced, I had begun to understand the compelling search among the

island’s citizens at this dawning of independence for authentic and enduring cultural markers that would become identity-affirming expressions demonstrating to the wider world who Dominicans are as their independent nation stepped upon the world stage.

The importance of musical expression in this context struck a responsive chord within me. Before arriving in Dominica, I had played the guitar, string bass and percussion instruments in a rock ‘n roll combo and with my high school orchestra and jazz band. I also worked as a disc jockey at my college radio station. With music in my blood, I was

quickly attracted to the island’s music scene. And was Dominica a hotbed of music in 1969!

There were the big-band calypso beats of The Swinging Stars and the vibrant performances of combos like The Gaylords and De Boys An Dem. Calypsonians were creating their deliberate rhymes of social and political commentary and bawdy compositions for ‘jump up’ and road march for the upcoming Carnival celebrations.

Steel drummers tuned their ‘pans’ and practiced for Carnival parades. Music on the radio featured the Mighty Sparrow and other Trinidadian calypsonians, the Merrymen of Barbados, and Byron Lee and the Dragonaires of Jamaica.

Linked closely to identity-affirming cultural expression were the acoustic offerings of goatskin drummers called La Peau Cabrit, and Jing Ping bands. Jing Ping was propelled by an accordion, drums, scrapers/rattles, and bamboo pipes. With their roots on plantations (called estates in Dominica), Jing Ping players performed songs that often included lyrical, call-response riffs sung in the island’s Afro-French patois, or Kreyòl, language. Having witnessed several La Peau Cabrit and Jing Ping groups perform on the 1969 National Day stage and the enthusiastic reception they received, the importance of this traditional music and the dances it supported, such as quadrille, as a vital part of Dominica’s cultural heritage was not lost on me.

I also had come to understand something about the significant yet embattled status of patois. I had been introduced to the language by a Dominican tutor during my Peace Corps training in Trinidad. From my teacher, I learned the context of the language: how it had evolved under slavery and was widely viewed, even in 1969, as inferior to the colonial language, English. Subsequently, I experienced how at least some Kreyòl speakers felt scorned when an outsider tried speaking to them in the language.

This lesson was thrust at me when, in my first days in Dominica, I approached several fishermen sitting by the sea at the village of Scotts Head, chatting among themselves in patois. Eager to put my nascent knowledge of the language to good use, I sauntered toward the men with a smile on my face and spoke in Kreyòl to inquire into their well- being. “Sa ka fet (how are you)?” I asked. Wow! Rather than receiving a friendly response in patois, I got a harsh response – in English. Did I think they were uneducated, they implied, when they spat back at me, “Speak to us in English.”

Our subsequent conversation was abbreviated and awkward. Retreating from the men, who I could hear resuming their conversation in Kreyòl, I had an insight into the fraught issues surrounding patois, while at the same time recognizing its importance as a marker of Dominican identity.

A Song is Born

Let’s go back to the veranda in Pottersville….

With all these revelations about Dominica swimming around my head, I was moved on that November 1969 evening to pick up my guitar and start strumming. Within an hour, I had come up with a ballad about Dominica with five verses, which I wrote as an ode to the island and its people. The final verse was in patois.

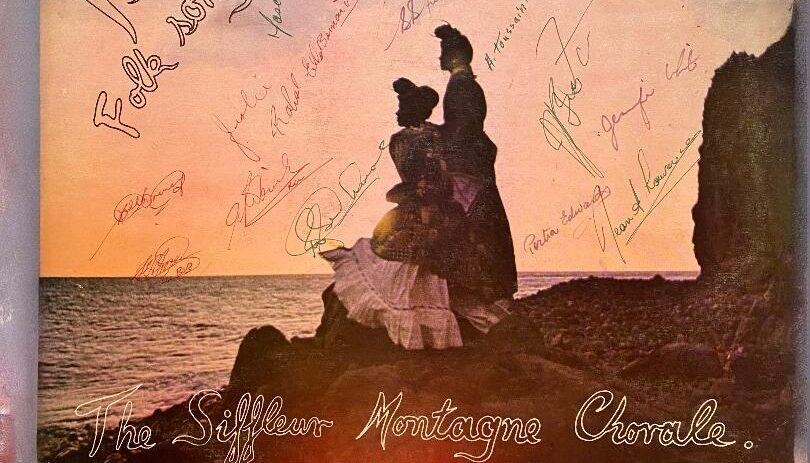

Shortly after arriving in Dominica, I met someone who would become an essential player in the story of my song. Jean Lawrence led a folk singing group formed towards the end of 1967 called the Siffleur Montagne Chorale, named after Dominica’s Mountain Whistler, a bird whose beautiful haunting song occupied the deep recesses of the island’s interior forests. Jean and the two dozen or so young women and men of the group were collecting traditional Dominican folk songs, writing new ones that mirrored the island’s rich culture, and performing in villages throughout the island. The venue at which I first heard their vocal majesty was on the National Day stage.

A few days after my solo musical reflection on the veranda, I crossed paths with Jean and told her about my composition. Might she be interested in it for the chorale, I wondered? To her everlasting credit, Jean didn’t dismiss me as some impulsive, or even worse, know-it-all newcomer to the island, but rather responded that yes, she would be interested. She invited me – with my guitar – to her home to play it for her, which I did, strumming the melody and singing the lyrics to the best of my ability. I should mention that songwriting came easier to me than singing. Jean liked what she heard. I left her with my music and lyrics. She took the ballad and wrote a moving vocal arrangement for the chorale, and the song became included in their performance list.

In 1971, 18 or so members of the Siffleur Montagne Chorale traveled to Trinidad and recorded their first album, Island Magic: Folk Songs of Dominica. The LP was released in Dominica in October of that year. The collection is comprised of mostly traditional Dominican folk songs and several of Jean’s compositions. My song is included in the album. Six of the album’s 11 tracks are in patois, including such favorites as Pa Embété Mon and Kai Voleurs. Pas Quittez Yo Prend Dominique, Jean’s composition celebrating Dominica’s history and culture, is sung mostly in English with a patois chorus. Island Magic: Folk Songs of Dominica became an instant hit in Dominica. It also struck a chord regionally, particularly in St. Lucia, where Kreyòl was also spoken widely and where cultural identity markers were equally being sought in advance of independence.

Although I was never a performing member of the chorale, my presence among its members was warmly embraced. On Sunday, February 21 , 1972, for example, we gathered after dark at my home in Loubiere village, where I then resided, to prepare for the arrival of J’ouvert, the traditional early morning street party that officially launches Carnival. Our long night ended with a pre-dawn Carnival march toward Roseau.

Singing joyously as we headed toward town, we also left a trail of the bleached flour that we had liberally doused on each other, as per J’ouvert’s tradition.

In August 1972, the Siffleur Montagne Chorale took their show on the road as part of Dominica’s delegation to the inaugural CARIFESTA regional arts festival, held that year in Georgetown, Guyana. I did not travel as part of the chorale but was in Georgetown nevertheless as a member of the People’s Action Theatre, also part of the Dominica

delegation. PAT, under the leadership of Alwin Bully, was selected to represent Dominica with a performance of Daniel ‘Papa Dee’ Caudeiron’s timely and popular play, Speak, Brother, Speak. I played the part of a retrograde White estate owner who could not accept social change. Our performances were critically acclaimed at the arts festival. The Siffleur Montagne Chorale was also a big hit at the festival with their uplifting performances that underscored the vibrancy of Dominica’s culture and its emerging national identity.