Image by Editor.

– Advertisement –

In the 1970s, West Indies cricketers faced racist abuse abroad but were treated as heroes at home.

Their World Cup wins in 1975 and 1979 made them symbols of pride and resistance, proving that players from small Caribbean islands could defeat the world’s best.

In a recent interview on The Rest is Politics podcast, Guyana’s president Irfaan Ali argued that international cricket authorities deliberately changed the rules on fast bowling in the 1990s to blunt the dominance of the West Indies.

He said the team’s fearsome pace attack, which terrorised batsmen worldwide for nearly two decades, was so effective that new restrictions were introduced to limit short-pitched deliveries and protect opposing players.

The dominance of West Indian fast bowlers at the time led to the adoption of helmets and other protective equipment to protect batsmen from injury. Up to that point batsmen had played bare-headed, some of them wearing glasses, which would be unthinkable today.

President Ali described these changes as a form of discrimination that undermined the Caribbean’s greatest strength and tilted the balance of the game against the once all-conquering West Indies side.

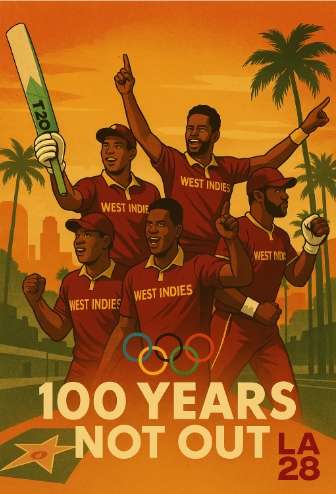

This year, St Vincent and the Grenadines hosted the first Emancipation Cricket Festival. Culture and tourism minister Carlos James said the event shows the link between emancipation, resistance, and cricket.

He argued that sport and politics are tied together, and that reviving love for cricket could help today’s struggling West Indies team.

Prime minister Ralph Gonsalves called cricket a tool for liberation, saying the Caribbean took a colonial game and transformed it into a weapon for freedom and identity. But despite the history, Caricom, the 15-nation regional body, has warned that it is “deeply concerned” about the decline of cricket in the region. The bloc called the sport a “public good” and said poor performances are a serious warning sign.

West Indies legend Sir Clive Lloyd, who twice lifted the World Cup, said Caricom’s support was welcome, and called for more funding. Former player Kesrick Williams added that younger players are losing interest and that cricket must be brought back into everyday life.

To inspire the new generation, Caricom hopes to involve surviving legends of the 1970s, who remain powerful role models.

Commemorative stamps of these cricketing icons were recently issued in St Vincent and the Grenadines, celebrating their role in Caribbean history.

Many in the region say one of the biggest problems is that the Caribbean does not have the money or facilities to train young players to a world-class standard.

Coaching programs are underfunded, pitches and equipment are limited, and school cricket has declined in many islands. Talented youngsters often have to leave for England, Australia, or North America to get proper training, meaning the best players are developed abroad instead of at home.

This creates a cycle where local cricket systems remain weak, and young athletes see their future only if they move overseas.

– Advertisement –